Rocklin’s Chinese-American Legacy (Part 1)

How Chinese Americans Built California, and the History of Violence They Encountered

This year the City of Rocklin celebrates our city’s 130th anniversary, which is a time to celebrate our City’s accomplishments, anticipate its bright future, and share in our community spirit. But it is also a time to reflect on our past and the place our City had in the history of California and its diverse population.

The Forgotten Rocklin Chinatown

Today Chinatowns in San Francisco and Los Angeles are world-famous tourist hotspots, featuring distinct Asian cuisine and events. Chinese immigration to the United States was widespread in California in the 1860s, and nearly every city in Placer County, including Rocklin, hosted growing communities of Chinese immigrants. Yet today, the only remnants of these once thriving Chinese American neighborhoods are a few buildings and the occasional historical marker.

This 2-part series commemorating May as AAPI Heritage Month celebrates Chinese culture in the Golden State, explores the Chinese contribution to California’s success, and delves into the lost history of Rocklin’s Chinatown.

Chinese Come to California

Local Chinatowns were formed during a wave of Chinese immigration to California after the Gold Rush. Over 2.5 million Chinese individuals fled their home in the 1850s and 1860s as a result of the devastating Taiping Rebellion that took an estimated 20 million lives in China. Like most immigrants to the United States, Chinese immigrants sought stable work, safety and security, and a means of support for their families in a new country.

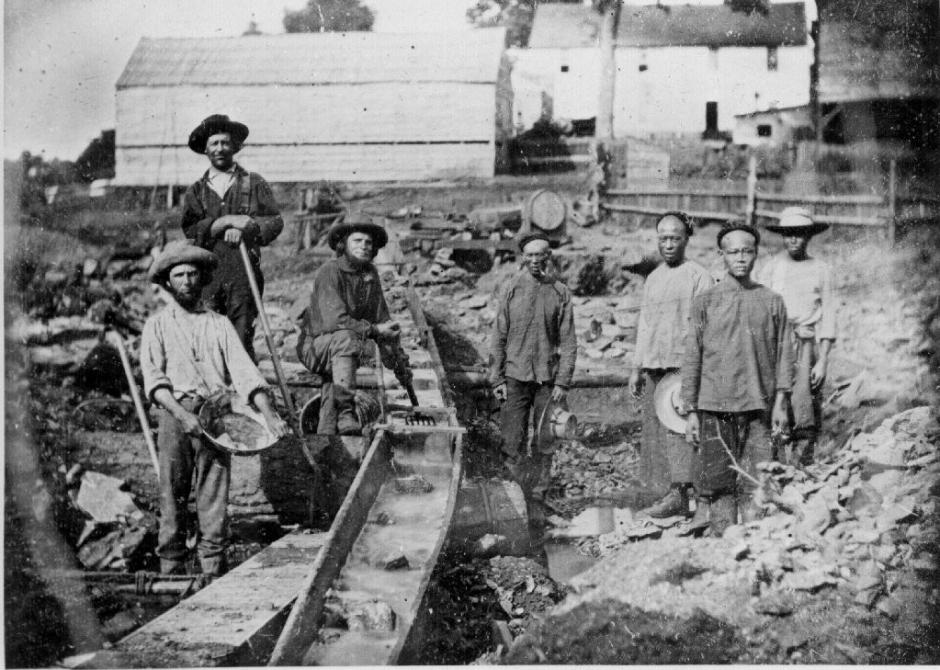

Chinese immigrants found work in mining, agriculture, forestry, and the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. In new frontier communities, they operated general stores, restaurants, and laundries. Their contributions to the economy and wealth of the Golden State should not be underestimated, but they are often forgotten in the retelling of the history of the West.

How Chinese Immigrants Built the Transcontinental Railroad

From 1863 to 1869, roughly 15,000-20,000 Chinese immigrants worked to build the nation’s first Transcontinental Railroad. The job was back-breaking, dangerous, and unforgiving. Freezing winters, scorching summers, accidental explosions, landslides, and disease killed many workers as they laid miles of tracks a day, built roadbeds, and drilled dynamite into sheer cliffs.

Initially, the Central Pacific Railroad was reluctant to hire Chinese immigrants. But labor shortages and the tight timeframe of the project pressured Central Pacific Railroad Director, Charles Crocker, to hire Chinese workers when only a few hundred white laborers responded to ads for the jobs available.

By 1867, 90% of railroad workers were Chinese. Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, former California Governor, and President of the Central Pacific Railroad, told Congress in 1865 that the contribution of the Chinese was irreplaceable (qtd. from The Industrial Revolution in America by Kevin Hillstrom):

Without them, it would be impossible to complete the western portion of this great national enterprise, within the time required by the Acts of Congress.

Despite the contribution of Chinese laborers, they were poorly treated and unfairly paid. Stanford University Professor Gordon Chang (author of Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad) points out that, “Chinese received 30-50% lower wages than whites for the same job and they had to pay for their own food stuffs.” While the railroad company provided its white laborers room and board in train cars, Chinese workers had to support themselves and live in tents outside.

Chinese American Contribution to California’s Agricultural Wealth

In addition to the railroad, Chinese labor significantly contributed to the wealth of the Central Valley by way of agriculture. The land that was once free and home to many California Native American tribes, including the Nisenan, Miwok, and Maidu (who lived in land that today includes Rocklin and Roseville), was sold in large tracts to elite, wealthy land owners.

University of Delaware professor Jean Pfaelzer and author of Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans credits the work of these Chinese Americans to the economic success of agricultural California:

The Chinese would build the infrastructure of a new county, dynamiting roads, clearing fields, digging ditches to supply water to the mines, and constructing hundreds of miles of stone fences.

In Rocklin, Joel Parker Whitney, purchased 18,000 acres of land in the 1860s and 1870s and became one of Placer County’s wealthiest people. Whitney hired approximately 1,000 Chinese laborers to do the work of road building, bridge building, fruit cultivation, and construction on the land.

Despite the importance of Chinese work to the wealth accumulated by California’s growing land-owning class, they were consistently the victim of discriminatory laws and practices and an increasing amount of racist violence from their non-Chinese neighbors, and were paid a fraction of the pay of white workers.

As the 1800s wore on, the gold mines that drew many settlers and immigrants to California began to dry up and jobs in the railroad and agriculture became increasingly scarce. A depression in the 1870s swept the country and bankrupted the largest bank in the nation at the time, Jay Cooke and Company. The difficult jobs on orchards and lumbermills suddenly became lucrative––the same jobs often occupied by Chinese immigrants.

In Los Angeles in 1871, violence broke out against Chinese, sparking a wave of hate that would spread all the way to the small growing towns of Rocklin, Roseville, and Loomis.

Part 2 of this series will be available next week. For more resources on Chinese American history in California and Rocklin, visit the Rocklin Historical Society, read Joel Parker Whitney’s memoir Reminiscences of a Sportsman, or check out Jean Pfaelzer’s Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans at the Rocklin Library.